Culloden Battlefield on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Culloden Battlefield Memorial Project

Cumberland's dispatch from the battle, published in the London Gazette

Controversy over the redevelopment of the NTS visitor centre at Culloden

Battle of Culloden Moor

Ghosts of Culloden including the Great Scree and Highlander Ghost

The "French Stone" at Culloden

*

by Daniel Paterson, 1746

"Plan of the Battle of Culloden"

by Anon, ca 1748

"Plan of the battle of Collodin ..."

by Jasper Leigh Jones, 1746

"A plan of the Battle of Culloden and the adjacent country, shewing the incampment of the English army at Nairn and the march of the Highlanders in order to attack them by night"

by John(?) Finlayson, 1746(?) {{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Culloden 1746 in Great Britain 1746 in Scotland Culloden Culloden History of the Scottish Highlands Culloden Museums in Highland (council area) Military and war museums in Scotland History museums in Scotland National Trust for Scotland properties Culloden

The Battle of Culloden (; gd, Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the

Apart from a skirmish at Clifton Moor, the Jacobite army evaded pursuit and crossed back into Scotland on 20 December. Entering and returning from England were considerable military achievements, and morale was high. The Jacobite strength increased to over 8,000 with the addition of a substantial north-eastern contingent under Lord Lewis Gordon, as well as Scottish and Irish regulars in French service. French-supplied artillery was used to besiege Stirling Castle, the strategic key to the Highlands. On 17 January, the Jacobites dispersed a relief force under

Apart from a skirmish at Clifton Moor, the Jacobite army evaded pursuit and crossed back into Scotland on 20 December. Entering and returning from England were considerable military achievements, and morale was high. The Jacobite strength increased to over 8,000 with the addition of a substantial north-eastern contingent under Lord Lewis Gordon, as well as Scottish and Irish regulars in French service. French-supplied artillery was used to besiege Stirling Castle, the strategic key to the Highlands. On 17 January, the Jacobites dispersed a relief force under

The Jacobite Army is often assumed to have been largely composed of Gaelic-speaking Catholic Highlanders: in reality nearly a quarter of the rank and file were recruited in

The Jacobite Army is often assumed to have been largely composed of Gaelic-speaking Catholic Highlanders: in reality nearly a quarter of the rank and file were recruited in

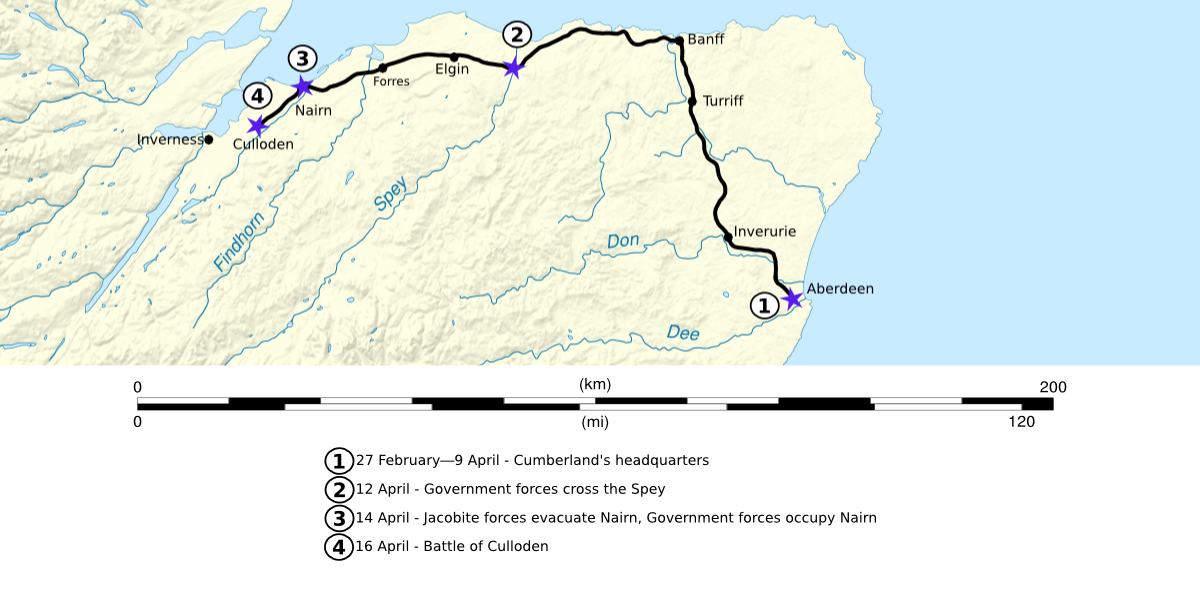

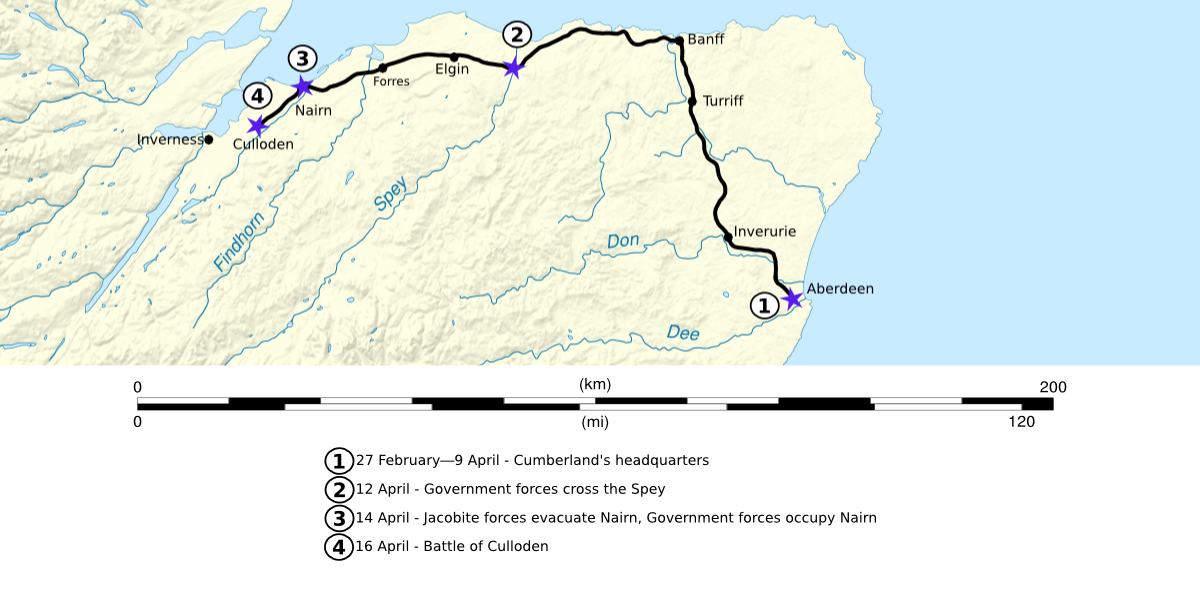

After the defeat at Falkirk Muir, Cumberland arrived in Scotland in January 1746 to take command of government forces. Deciding to wait out the winter, he moved his main army northwards to

After the defeat at Falkirk Muir, Cumberland arrived in Scotland in January 1746 to take command of government forces. Deciding to wait out the winter, he moved his main army northwards to

After the abortive night attack, the Jacobites formed up in substantially the same battle order as the previous day, with the Highland regiments forming the first line. They faced north-east over common grazing land, with the Water of Nairn about 1 km to their right. Their left wing, anchored on the Culloden Park walls, was under the command of the titular Duke of Perth, James Drummond; his brother John Drummond commanded the centre. The right wing, flanked by the Culwhiniac enclosure walls, was led by Murray. Behind them, the Low Country regiments were drawn up in column, in accordance with French practice. During the morning, snow and hail "started falling very thick" onto the already wet ground and later turned to rain, but the weather turned fair as the battle started.

Cumberland's army had struck camp and become underway by , leaving the main Inverness road and marching across country. By , the Jacobites finally saw them approaching at a distance of around . At from the Jacobite position, Cumberland gave the order to form line, and the army marched forward in full battle order.Pittock (2016) p.79 John Daniel, an Englishman serving with Charles's army, recorded that on seeing the government troops the Jacobites began to "

After the abortive night attack, the Jacobites formed up in substantially the same battle order as the previous day, with the Highland regiments forming the first line. They faced north-east over common grazing land, with the Water of Nairn about 1 km to their right. Their left wing, anchored on the Culloden Park walls, was under the command of the titular Duke of Perth, James Drummond; his brother John Drummond commanded the centre. The right wing, flanked by the Culwhiniac enclosure walls, was led by Murray. Behind them, the Low Country regiments were drawn up in column, in accordance with French practice. During the morning, snow and hail "started falling very thick" onto the already wet ground and later turned to rain, but the weather turned fair as the battle started.

Cumberland's army had struck camp and become underway by , leaving the main Inverness road and marching across country. By , the Jacobites finally saw them approaching at a distance of around . At from the Jacobite position, Cumberland gave the order to form line, and the army marched forward in full battle order.Pittock (2016) p.79 John Daniel, an Englishman serving with Charles's army, recorded that on seeing the government troops the Jacobites began to "

The Jacobite right was particularly hard hit by a volley from the government regiments at nearly point-blank range, but many of its men still reached the government lines, and for the first time, a battle was decided by a direct clash between charging Highlanders and formed infantry equipped with muskets and socket bayonets. The brunt of the Jacobite impact, led by Lochiel's regiment, was taken by only two government regiments: Barrell's 4th Foot and Dejean's 37th Foot. Barrell's lost 17 killed and suffered 108 wounded, out of a total of 373 officers and men. Dejean's lost 14 killed and had 68 wounded, with the unit's left wing taking a disproportionately-higher number of casualties. Barrell's regiment temporarily lost one of its two

The Jacobite right was particularly hard hit by a volley from the government regiments at nearly point-blank range, but many of its men still reached the government lines, and for the first time, a battle was decided by a direct clash between charging Highlanders and formed infantry equipped with muskets and socket bayonets. The brunt of the Jacobite impact, led by Lochiel's regiment, was taken by only two government regiments: Barrell's 4th Foot and Dejean's 37th Foot. Barrell's lost 17 killed and suffered 108 wounded, out of a total of 373 officers and men. Dejean's lost 14 killed and had 68 wounded, with the unit's left wing taking a disproportionately-higher number of casualties. Barrell's regiment temporarily lost one of its two  With the Jacobites who were left under Perth failing to advance further, Cumberland ordered two troops of Cobham's 10th Dragoons to ride them down. The boggy ground, however, impeded the cavalry, and they turned to engage the Irish Picquets whom Sullivan and Lord John Drummond had brought up in an attempt to stabilise the deteriorating Jacobite left flank. Cumberland later wrote: "They came running on in their wild manner, and upon the right where I had placed myself, imagining the greatest push would be there, they came down there several times within a hundred yards of our men, firing their pistols and brandishing their swords, but the Royal Scots and Pulteneys hardly took their fire-locks from their shoulders, so that after those faint attempts they made off; and the little squadrons on our right were sent to pursue them".Roberts (2002), p. 173.

With the Jacobites who were left under Perth failing to advance further, Cumberland ordered two troops of Cobham's 10th Dragoons to ride them down. The boggy ground, however, impeded the cavalry, and they turned to engage the Irish Picquets whom Sullivan and Lord John Drummond had brought up in an attempt to stabilise the deteriorating Jacobite left flank. Cumberland later wrote: "They came running on in their wild manner, and upon the right where I had placed myself, imagining the greatest push would be there, they came down there several times within a hundred yards of our men, firing their pistols and brandishing their swords, but the Royal Scots and Pulteneys hardly took their fire-locks from their shoulders, so that after those faint attempts they made off; and the little squadrons on our right were sent to pursue them".Roberts (2002), p. 173.

The stand by the French regulars gave Charles and other senior officers time to escape. Charles seems to have been rallying Perth's and Glenbucket's regiments when Sullivan rode up to Captain Shea, commander of his bodyguard: "Yu see all is going to pot. Yu can be of no great succor, so before a general deroute wch will soon be, Seize upon the Prince & take him off ...". Contrary to government depictions of Charles as a coward, he yelled "they won't take me alive!" and called for a final charge into the government lines: Shea, however, followed Sullivan's advice and led Charles from the field, accompanied by Perth and Glenbucket's regiments.

From that point onward, the fleeing Jacobite forces were split into several groups: the Lowland regiments retired southwards, making their way to

The stand by the French regulars gave Charles and other senior officers time to escape. Charles seems to have been rallying Perth's and Glenbucket's regiments when Sullivan rode up to Captain Shea, commander of his bodyguard: "Yu see all is going to pot. Yu can be of no great succor, so before a general deroute wch will soon be, Seize upon the Prince & take him off ...". Contrary to government depictions of Charles as a coward, he yelled "they won't take me alive!" and called for a final charge into the government lines: Shea, however, followed Sullivan's advice and led Charles from the field, accompanied by Perth and Glenbucket's regiments.

From that point onward, the fleeing Jacobite forces were split into several groups: the Lowland regiments retired southwards, making their way to

The morning after the Battle of Culloden, Cumberland issued a written order reminding his men that "the public orders of the rebels yesterday was to give us

The morning after the Battle of Culloden, Cumberland issued a written order reminding his men that "the public orders of the rebels yesterday was to give us  While in Inverness, Cumberland emptied the

While in Inverness, Cumberland emptied the

Today, a

Today, a  Since 2001, the site of the battle has undergone

Since 2001, the site of the battle has undergone

Colonel John William Sullivan

Commander-in-Chief North Britain: Lieutenant-General Henry Hawley See the following reference for source of tablesUnless noted elsewhere, units and unit sizes are from, Reid (2002), pp. 26–27. * Of the 16 British infantry battalions, 11 were English, 4 were Scottish (3 Lowland + 1 Highland), and 1 Irish battalion. * Of the 3 British battalions of horse (dragoons), 2 were English and 1 was Scottish.

* ''An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745'' (as shown in the infobox at the top of this page), by

* ''An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745'' (as shown in the infobox at the top of this page), by

*

*

in 1976.

* Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took ...

. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite army of Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

government force under Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland

Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (15 April 1721 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S..html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki> N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;"title="/nowiki>Old_Style_and_New_St ...

, on Drummossie Moor near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

. It was the last pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

fought on British soil.

Charles was the eldest son of James Stuart, the exiled Stuart claimant to the British throne. Believing there was support for a Stuart restoration in both Scotland and England, he landed in Scotland in July 1745: raising an army of Scots Jacobite supporters, he took Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

by September, and defeated a British government force at Prestonpans

Prestonpans ( gd, Baile an t-Sagairt, Scots language, Scots: ''The Pans'') is a small mining town, situated approximately eight miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Council area of East Lothian. The population as of is. It is near the si ...

. The government recalled 12,000 troops from the Continent to deal with the rising: a Jacobite invasion of England reached as far as Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

before turning back, having attracted relatively few English recruits.

The Jacobites, with limited French military support, attempted to consolidate their control of Scotland, where, by early 1746, they were opposed by a substantial government army. A hollow Jacobite victory at Falkirk failed to change the strategic situation: with supplies and pay running short and with the government troops resupplied and reorganised under the Duke of Cumberland, son of British monarch George II, the Jacobite leadership had few options left other than to stand and fight. The two armies eventually met at Culloden, on terrain that gave Cumberland's larger, well-rested force the advantage. The battle lasted only an hour, with the Jacobites suffering a bloody defeat; between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobites were killed or wounded, while about 300 government soldiers were killed or wounded. While perhaps 5,000 – 6,000 Jacobites remained in arms in Scotland, the leadership took the decision to disperse, effectively ending the rising.

Culloden and its aftermath continue to arouse strong feelings. The University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

awarded the Duke of Cumberland an honorary doctorate, but many modern commentators allege that the aftermath of the battle and subsequent crackdown on Jacobite sympathisers were brutal, earning Cumberland the sobriquet

A sobriquet ( ), or soubriquet, is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another, that is descriptive. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym, as it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name, without the need of expla ...

"Butcher". Efforts were subsequently made to further integrate the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

into the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

; civil penalties were introduced to undermine the Scottish clan

A Scottish clan (from Goidelic languages, Gaelic , literally 'children', more broadly 'kindred') is a kinship group among the Scottish people. Clans give a sense of shared identity and descent to members, and in modern times have an official ...

system, which had provided the Jacobites with the means to rapidly mobilise an army.

Background

Queen Anne, the last monarch of theHouse of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

, died in 1714, with no surviving children. Under the terms of the Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

, she was succeeded by her second cousin

Most generally, in the lineal kinship system used in the English-speaking world, a cousin is a type of familial relationship in which two relatives are two or more familial generations away from their most recent common ancestor. Commonly, ...

George I of the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house orig ...

, who was a descendant of the Stuarts through his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

, a daughter of James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

. Many, however, particularly in Scotland and Ireland, continued to support the claim to the throne of Anne's exiled half-brother, James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, who was excluded from the succession under the Act of Settlement for his Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

.

On 23 July 1745 James's son Charles Edward Stuart landed on Eriskay

Eriskay ( gd, Èirisgeigh), from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland with a population of 143, as of the 2011 census. It lies between South Uist and Barra and is ...

in the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

in an attempt to reclaim the throne for his father and was accompanied only by the "Seven Men of Moidart

The Seven Men of Moidart, in Jacobite folklore, were seven followers of Charles Edward Stuart who accompanied him at the start of his 1745 attempt to reclaim the thrones of Great Britain and Ireland for the House of Stuart. The group included E ...

". Most of his Scottish supporters advised he return to France, but his persuasion of Donald Cameron of Lochiel

Donald Cameron of Lochiel (c. 1695 – 1748), popularly known as the Gentle Lochiel, was a Scottish Jacobite and hereditary chief of Clan Cameron, traditionally loyal to the exiled House of Stuart. His father John was permanently exiled after ...

to back him encouraged others to commit, and the rebellion was launched, with the raising of the Jacobite standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object th ...

at Glenfinnan

Glenfinnan ( gd, Gleann Fhionnain ) is a hamlet in Lochaber area of the Highlands of Scotland. In 1745 the Jacobite rising began here when Prince Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie") raised his standard on the shores of Loch Shiel ...

on 19 August. The Jacobite army entered Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

on 17 September. James was proclaimed King of Scotland the next day and Charles his regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

. Attracting more recruits, the Jacobites comprehensively defeated a government force at the Battle of Prestonpans

The Battle of Prestonpans, also known as the Battle of Gladsmuir, was fought on 21 September 1745, near Prestonpans, in East Lothian, the first significant engagement of the Jacobite rising of 1745.

Jacobite forces, led by the Stuart exile C ...

on 21 September. The London government now recalled the Duke of Cumberland, the King's younger son and commander of the British army in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

, along with 12,000 troops.

The Prince's Council, a committee formed of 15 to 20 senior leaders, met on 30 and 31 October to discuss plans to invade England. The Scots wanted to consolidate their position; they were willing to assist an English rising or French landing but not on their own.Riding, p.199. For Charles, the main prize was England;. He argued that removing the Hanoverians would guarantee an independent Scotland and assured the Scots that the French were planning to land in southern England and that thousands of English supporters would join him once across the border.

Despite their doubts, the Council agreed to the invasion on condition that the promised English and French support was forthcoming. The Jacobite Army entered England on 8 NovemberDuffy, p.223 and captured Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

on 15 November, continued south through Preston and Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and reached Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

on 4 December. There had been no sign of a French landing or any significant number of English recruits, and the Jacobites risked being caught between two armies, each one twice their size: Cumberland's, advancing north from London and George Wade

Field Marshal George Wade (1673 – 14 March 1748) was a British Army officer who served in the Nine Years' War, War of the Spanish Succession, Jacobite rising of 1715 and War of the Quadruple Alliance before leading the construction of bar ...

's moving south from Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

. Despite Charles' opposition, the Council was overwhelmingly in favour of retreat and turned northwards the next day.Riding, pp. 304–305

Apart from a skirmish at Clifton Moor, the Jacobite army evaded pursuit and crossed back into Scotland on 20 December. Entering and returning from England were considerable military achievements, and morale was high. The Jacobite strength increased to over 8,000 with the addition of a substantial north-eastern contingent under Lord Lewis Gordon, as well as Scottish and Irish regulars in French service. French-supplied artillery was used to besiege Stirling Castle, the strategic key to the Highlands. On 17 January, the Jacobites dispersed a relief force under

Apart from a skirmish at Clifton Moor, the Jacobite army evaded pursuit and crossed back into Scotland on 20 December. Entering and returning from England were considerable military achievements, and morale was high. The Jacobite strength increased to over 8,000 with the addition of a substantial north-eastern contingent under Lord Lewis Gordon, as well as Scottish and Irish regulars in French service. French-supplied artillery was used to besiege Stirling Castle, the strategic key to the Highlands. On 17 January, the Jacobites dispersed a relief force under Henry Hawley

Henry Hawley (12 January 1685 – 24 March 1759) was a British army officer who served in the wars of the first half of the 18th century. He fought in a number of significant battles, including the Capture of Vigo in 1719, Dettingen, Fo ...

at the Battle of Falkirk Muir

The Battle of Falkirk Muir (Scottish Gaelic: ''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice''), also known as the Battle of Falkirk, took place on 17 January 1746 during the Jacobite rising of 1745. Although it resulted in a Jacobite victory, their inability to ...

although the siege made little progress.Riding, pp. 209–216

On 1 February, the siege of Stirling was abandoned, and the Jacobites withdrew to Inverness.Home, pp. 353–354 Cumberland's army advanced along the coast and entered Aberdeen on 27 February, and both sides halted operations until the weather improved.Riding, pp. 377–378 Several French shipments were received during the winter but the Royal Navy's blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

led to shortages of both money and food. When Cumberland left Aberdeen on 8 April, Charles and his officers agreed giving battle was their best option.

Opposing forces

Jacobite army

The Jacobite Army is often assumed to have been largely composed of Gaelic-speaking Catholic Highlanders: in reality nearly a quarter of the rank and file were recruited in

The Jacobite Army is often assumed to have been largely composed of Gaelic-speaking Catholic Highlanders: in reality nearly a quarter of the rank and file were recruited in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

, Forfarshire and Banffshire

Banffshire ; sco, Coontie o Banffshire; gd, Siorrachd Bhanbh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. The county town is Banff, although the largest settlement is Buckie to the west. It borders the Moray ...

, with another 20% from Perthshire

Perthshire (locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, ...

. By 1745, Catholicism was the preserve of a small minority, and large numbers of those who joined the Rebellion were Non-juring Episcopalians. Although the army was predominantly Scots, it contained a few English recruits plus significant numbers of Irish, Scottish and French professionals in French service with the Irish Brigade and '' Royal Ecossais''.

To mobilise an army quickly, the Jacobites had relied heavily on the traditional right retained by many Scottish landowners to raise their tenants for military service. This assumed limited, short-term warfare: a long campaign demanded greater professionalism and training, and the colonels of some Highland regiments considered their men to be uncontrollable.Harrington (1991), pp. 35–40. A typical 'clan' regiment was officered by the heavily-armed tacksmen, with their subtenants acting as common soldiers.Barthorp, Michael (1982). The Jacobite Rebellions 1689–1745. Men-at-arms series. p 17-18. Osprey Publishing. . The tacksmen served in the front rank, taking proportionately high casualties; the gentlemen of the Appin

Appin ( gd, An Apainn) is a coastal district of the Scottish West Highlands bounded to the west by Loch Linnhe, to the south by Loch Creran, to the east by the districts of Benderloch and Lorne, and to the north by Loch Leven. It lies north ...

Regiment numbered one-quarter of those killed and one-third of those wounded from their regiment.Reid (1997), p. 58. Many Jacobite regiments, notably those from the northeast, were organised and drilled more conventionally, but as with the Highland regiments were inexperienced and hurriedly trained.

The Jacobites started the campaign relatively poorly armed. Although Highlanders are often pictured equipped with a broadsword, targe

Targe (from Old Franconian ' 'shield', Proto-Germanic ' 'border') was a general word for shield in late Old English. Its diminutive, ''target'', came to mean an object to be aimed at in the 18th century.

The term refers to various types of shie ...

and pistol, this applied mainly to officers; most men seem to have been drilled in conventional fashion with muskets as their main weapon. As the campaign progressed, supplies from France improved their equipment considerably and by the time of Culloden, many were equipped with calibre

In guns, particularly firearms, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel bore – regardless of how or where the bore is measured and whether the finished bore match ...

French and Spanish firelocks.Reid (2006), pp. 20–22.

During the latter stage of the campaign, the Jacobites were reinforced by French regulars, mainly drawn from or detachments from regiments of the Irish Brigade along with a Franco-Irish cavalry unit, Fitzjames's Horse. Around 500 men from the Irish Brigade fought in the battle, around 100 of whom were thought to have been recruited from 6th (Guise's) Foot taken prisoner at Fort Augustus. The ''Royal Écossais'' also contained British deserters

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ar ...

; its commander attempted to raise a second battalion after the unit had arrived in Scotland.Reid (2006), pp. 22–23. Much of the Jacobite cavalry had been effectively disbanded due to a shortage of horses; Fitzjames', Strathallan's Horse, the Life Guards and the 'Scotch Hussars' retained a reduced presence at Culloden. The Jacobite artillery is generally regarded as playing little part in the battle, all but one of the cannon being 3-pounders.

Government army

Cumberland's army at Culloden comprised 16 infantry battalions, including four Scottish units and oneIrish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

.Reid (2002), p. ''author's note''. The bulk of the infantry units had already seen action at Falkirk, but had been further drilled, rested and resupplied since then.

Many of the infantry were experienced veterans of Continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' ( ...

service, but on the outbreak of the Jacobite rising, extra incentives were given to recruits to fill the ranks of depleted units. On 6 September 1745, every recruit who joined the Guards before 24 September was given £6, and those who joined in the last days of the month were given £4. In theory, a standard single-battalion British infantry regiment was 815 strong, including officers, but was often smaller in practice and at Culloden, the regiments were not much larger than about 400 men.Harrington (1991), pp. 25–29.

The government cavalry arrived in Scotland in January 1746. Many were not combat experienced, having spent the preceding years on anti-smuggling duties. A standard cavalryman had a Land Service pistol and a carbine, but the main weapon used by the British cavalry was a sword with a 35-inch blade.Harrington (1991), pp. 29–33.

The Royal Artillery vastly outperformed their Jacobite counterparts during the Battle of Culloden. However, until this point in the campaign, the government artillery had performed dismally. The main weapon of the artillery was the 3-pounder. This weapon had a range of and fired two kinds of shot: round iron and canister. The other weapon used was the Coehorn mortar. These had a calibre of inches (11 cm).Harrington (1991), p. 33.

Lead-up

After the defeat at Falkirk Muir, Cumberland arrived in Scotland in January 1746 to take command of government forces. Deciding to wait out the winter, he moved his main army northwards to

After the defeat at Falkirk Muir, Cumberland arrived in Scotland in January 1746 to take command of government forces. Deciding to wait out the winter, he moved his main army northwards to Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

: 5,000 Hessian

A Hessian is an inhabitant of the German state of Hesse.

Hessian may also refer to:

Named from the toponym

*Hessian (soldier), eighteenth-century German regiments in service with the British Empire

**Hessian (boot), a style of boot

**Hessian f ...

troops under Prince Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

were stationed around Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

to suppress a possible Jacobite offensive in that area. The weather had improved to such an extent by 8 April that Cumberland resumed the campaign. His army reached Cullen on 11 April, where it was joined by six further battalions and two cavalry regiments. On 12 April, Cumberland's force forded the Spey, which had been guarded by a 2,000-strong Jacobite detachment under Lord John Drummond, but Drummond retreated towards Elgin and Nairn

Nairn (; gd, Inbhir Narann) is a town and royal burgh in the Highland council area of Scotland. It is an ancient fishing port and market town around east of Inverness, at the point where the River Nairn enters the Moray Firth. It is the tradit ...

, rather than offer resistance, for which he was sharply criticised after the rising by several Jacobite memoirists. By 14 April, the Jacobites had evacuated Nairn, and Cumberland's army camped at Balblair just west of the town.Reid (2002), pp. 51–56.

Several significant Jacobite units were still ''en route'' or engaged far to the north, but on learning of the government advance, their main army of about 5,400 left its base at Inverness on 15 April and assembled in battle order at the estate of Culloden, 5 miles (8 km) to the east. The Jacobite leadership was divided on whether to give battle or abandon Inverness, but with most of their dwindling supplies stored in the town, there were few options left for holding their army together.Pittock (2016), p.58 The Jacobite adjutant-general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

, John O'Sullivan John O'Sullivan may refer to:

Sports

*John O'Sullivan (cricketer) (1918–1991), New Zealand cricketer

*John O'Sullivan (cyclist) (born 1933), Australian cyclist

*John O'Sullivan (footballer) (born 1993), Irish footballer for Accrington Stanley

*J ...

, identified a suitable site for a defensive action at Drummossie Moor, a stretch of open moorland between the walled enclosures of Culloden Parks to the north and those of Culwhiniac to the south.

Jacobite Lieutenant-General Lord George Murray stated that he "did not like the ground" at Drummossie Moor, which was relatively flat and open, and suggested an alternative steeply-sloping site near Daviot Castle

Daviot Castle was a 15th-century castle, about southeast of Inverness, Highland, Scotland, and west of the River Nairn at Daviot. Also known as Strathnairn Castle, its remains are designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

History

A castle was ...

. That was inspected by Brigadier Stapleton of the Irish Brigade and Colonel Ker on the morning of 15 April; they rejected it as the site was overlooked and the ground "mossy and soft". Murray's choice also failed to protect the road into Inverness, a key objective of giving battle. The issue had not been fully resolved by the time of the battle, and in the event, circumstances largely dictated the point at which the Jacobites formed line, some distance to the west of the site that had originally been chosen by Sullivan.

Night attack at Nairn

On 15 April, the government army celebrated Cumberland's 25th birthday by issuing two gallons ofbrandy

Brandy is a liquor produced by distilling wine. Brandy generally contains 35–60% alcohol by volume (70–120 US proof) and is typically consumed as an after-dinner digestif. Some brandies are aged in wooden casks. Others are coloured with ...

to each regiment.Harrington (1991), p. 44. At Charles's suggestion, the Jacobites tried that evening to repeat the success of Prestonpans by carrying out a night attack on the government encampment.

Murray proposed that they set off at dusk and march to Nairn; he planned to have the right wing of the first line attack Cumberland's rear while the Duke of Perth with the left wing would attack the government's front. In support of Perth, Lord John Drummond and Charles would bring up the second line. The Jacobite force, however, started out well after dark, partly out of concerns of being spotted by ships of the Royal Navy then in the Moray Firth

The Moray Firth (; Scottish Gaelic: ''An Cuan Moireach'', ''Linne Mhoireibh'' or ''Caolas Mhoireibh'') is a roughly triangular inlet (or firth) of the North Sea, north and east of Inverness, which is in the Highland council area of north of Scotl ...

. Murray led it across country with the intention of avoiding government outposts. Murray's onetime '' aide-de-camp'', James Chevalier de Johnstone

James Johnstone (1719 – c. 1791), also known as Chevalier de Johnstone or Johnstone de Moffatt, was the son of an Edinburgh merchant. He escaped to France after participating in the 1745 Rising; in 1750, he was commissioned in the colonial arm ...

later wrote that "this march across country in a dark night which did not allow us to follow any track asaccompanied with confusion and disorder".

When the leading troop had reached Culraick, still from where Murray's wing was to cross the River Nairn and encircle the town, there was only one hour left before dawn. After a heated council with other officers, Murray concluded that there was not enough time to mount a surprise attack and that the offensive should be aborted. Sullivan went to inform Charles Edward Stuart of the change of plan but missed him in the dark. Meanwhile, instead of retracing his path back, Murray led his men left down the Inverness road. In the darkness, while Murray led one third of the Jacobite forces back to camp, the other two thirds continued towards their original objective, unaware of the change in plan. One account of that night even records as Perth's men having made contact with government troops before they realised that the rest of the Jacobite force had turned home. A few historians, such as Jeremy Black and Christopher Duffy

Christopher Duffy (1936 – 16 November 2022) was a British military historian.

Duffy read history at Balliol College, Oxford, where he graduated in 1961 with the DPhil. Afterwards, he taught military history at the Royal Military Academy Sandhu ...

, have suggested that if Perth had carried on, the night attack might have remained viable, but most have disagreed, as perhaps only 1,200 of the Jacobite force accompanied him.

Not long after the exhausted Jacobite forces had made it back to Culloden, an officer of Lochiel's regiment, who had been left behind after falling asleep in a wood, arrived with a report of advancing government troops.Reid (2002), pp. 56–58. By then, many Jacobite soldiers had dispersed in search of food or returned to Inverness, and others were asleep in ditches and outbuildings. Several hundred of their army may have missed the battle.

Battle

After the abortive night attack, the Jacobites formed up in substantially the same battle order as the previous day, with the Highland regiments forming the first line. They faced north-east over common grazing land, with the Water of Nairn about 1 km to their right. Their left wing, anchored on the Culloden Park walls, was under the command of the titular Duke of Perth, James Drummond; his brother John Drummond commanded the centre. The right wing, flanked by the Culwhiniac enclosure walls, was led by Murray. Behind them, the Low Country regiments were drawn up in column, in accordance with French practice. During the morning, snow and hail "started falling very thick" onto the already wet ground and later turned to rain, but the weather turned fair as the battle started.

Cumberland's army had struck camp and become underway by , leaving the main Inverness road and marching across country. By , the Jacobites finally saw them approaching at a distance of around . At from the Jacobite position, Cumberland gave the order to form line, and the army marched forward in full battle order.Pittock (2016) p.79 John Daniel, an Englishman serving with Charles's army, recorded that on seeing the government troops the Jacobites began to "

After the abortive night attack, the Jacobites formed up in substantially the same battle order as the previous day, with the Highland regiments forming the first line. They faced north-east over common grazing land, with the Water of Nairn about 1 km to their right. Their left wing, anchored on the Culloden Park walls, was under the command of the titular Duke of Perth, James Drummond; his brother John Drummond commanded the centre. The right wing, flanked by the Culwhiniac enclosure walls, was led by Murray. Behind them, the Low Country regiments were drawn up in column, in accordance with French practice. During the morning, snow and hail "started falling very thick" onto the already wet ground and later turned to rain, but the weather turned fair as the battle started.

Cumberland's army had struck camp and become underway by , leaving the main Inverness road and marching across country. By , the Jacobites finally saw them approaching at a distance of around . At from the Jacobite position, Cumberland gave the order to form line, and the army marched forward in full battle order.Pittock (2016) p.79 John Daniel, an Englishman serving with Charles's army, recorded that on seeing the government troops the Jacobites began to "huzza

Huzzah (sometimes written ''hazzah''; originally spelled huzza and pronounced huz-ZAY, now often pronounced as huz-ZAH; in most modern varieties of English hurrah or hooray) is, according to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED''), "appar ...

and bravado them" but without response: "on the contrary, they continued proceding, like a deep sullen river". Once within 500 metres, Cumberland moved his artillery up through the ranks.

As Cumberland's forces formed into line of battle, it became clear that their right flank was in an exposed position, and Cumberland moved up additional cavalry and other units to reinforce it.Pittock (2016) p.83 In the Jacobite lines, Sullivan moved two battalions of Lord Lewis Gordon's regiment to cover the walls at Culwhiniac against a possible flank attack by government dragoons. Murray also moved the Jacobite right slightly forwards. That "changement", as Sullivan called it, had the unintended result of skewing the Jacobite line and opening gaps and so Sullivan ordered Perth's, Glenbucket's and the Edinburgh Regiment from the second line to the first. While the Jacobites' front rank now substantially outnumbered that of Cumberland, their reserve was further depleted, increasing their reliance on a successful initial attack.Pittock (2016) p.85

Artillery exchange

At approximately 1 pm, Finlayson's Jacobite batteries opened fire; possibly in response to Cumberland sending forward Lord Bury to within 100 m of the Jacobite lines to "ascertain the strength of their battery".Pittock (2016) p.86 The government artillery responded shortly afterwards. Some later Jacobite memoirs suggest that their troops were then subjected to artillery bombardment for 30 minutes or more while Charles delayed an advance, but government accounts suggest a much shorter exchange before the Jacobites attacked. Campbell of Airds, in the rear, timed it at 9 minutes, but Cumberland's aide-de-camp Yorke suggested only 2 or 3 minutes. The duration implies that the government artillery is unlikely to have fired more than thirty rounds at extreme range: statistical analysis concludes that would have caused only 20–30 Jacobite casualties at that stage, rather than the hundreds suggested by some accounts.Jacobite advance

Shortly after 1 pm, Charles issued an order to advance, which Colonel Harry Kerr of Graden first took to Perth's regiment, on the extreme left. He then rode down the Jacobite line giving orders to each regiment in turn. Sir John MacDonald and Brigadier Stapleton were also sent forward to repeat the order.Pittock (2016) p.87 As the Jacobites left their lines, the government gunners switched tocanister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel artillery ammunition. Canister shot has been used since the advent of gunpowder-firing artillery in Western armies. However, canister shot saw particularly frequent use on land and at sea in the various ...

, which was augmented by fire from the coehorn

A Coehorn (also spelled ''cohorn'') is a lightweight mortar originally designed by Dutch military engineer Menno van Coehoorn.

Concept and design

Van Coehoorn came to prominence during the 1688–97 Nine Years War, whose tactics have been su ...

mortars situated behind the government front line. As there was no need for careful aiming when canister was used, the rate of fire increased dramatically, and the Jacobites found themselves advancing into heavy fire.Pittock (2016) p.86

On the Jacobite right, the Atholl

Atholl or Athole ( gd, Athall; Old Gaelic ''Athfhotla'') is a large historical division in the Scottish Highlands, bordering (in anti-clockwise order, from Northeast) Marr, Badenoch, Lochaber, Breadalbane, Strathearn, Perth, and Gowrie. Histor ...

Brigade, Lochiel's and the Appin Regiment left their start positions and charged towards Barrell's and Munro's regiments. Within a few hundred yards, however, the centre regiments, Lady Mackintosh's and Lovat's, had begun to swerve rightwards to try to avoid canister fire or to follow the firmer ground along the road running diagonally across Drummossie Moor. The five regiments became entangled as a single mass, converging on the government left. The confusion was worsened when the three largest regiments lost their commanding officers, all at the front of the advance: MacGillivray and MacBean of Lady Mackintosh's both went down; Inverallochie of Lovat's fell and Lochiel had his ankles broken by canister within a few yards of the government lines.

The Jacobite left, by contrast, advanced much more slowly, hampered by boggy ground and by having several hundred yards further to cover. According to the account of Andrew Henderson, Lord John Drummond walked across the front of the Jacobite lines to try and tempt the government infantry into firing early, but they maintained their discipline. The three MacDonald regiments (Keppoch's, Clanranald's and Glengarry's) stalled before resorting to ineffectual long-range musket fire. They also lost senior officers, as Clanranald was wounded and Keppoch killed. The smaller units on their right (Maclachlan's Regiment and Chisholm's and Monaltrie's battalions) advanced into an area swept by artillery fire and suffered heavy losses before falling back.

Engagement of government left wing

The Jacobite right was particularly hard hit by a volley from the government regiments at nearly point-blank range, but many of its men still reached the government lines, and for the first time, a battle was decided by a direct clash between charging Highlanders and formed infantry equipped with muskets and socket bayonets. The brunt of the Jacobite impact, led by Lochiel's regiment, was taken by only two government regiments: Barrell's 4th Foot and Dejean's 37th Foot. Barrell's lost 17 killed and suffered 108 wounded, out of a total of 373 officers and men. Dejean's lost 14 killed and had 68 wounded, with the unit's left wing taking a disproportionately-higher number of casualties. Barrell's regiment temporarily lost one of its two

The Jacobite right was particularly hard hit by a volley from the government regiments at nearly point-blank range, but many of its men still reached the government lines, and for the first time, a battle was decided by a direct clash between charging Highlanders and formed infantry equipped with muskets and socket bayonets. The brunt of the Jacobite impact, led by Lochiel's regiment, was taken by only two government regiments: Barrell's 4th Foot and Dejean's 37th Foot. Barrell's lost 17 killed and suffered 108 wounded, out of a total of 373 officers and men. Dejean's lost 14 killed and had 68 wounded, with the unit's left wing taking a disproportionately-higher number of casualties. Barrell's regiment temporarily lost one of its two colours

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are associ ...

. Major-General Huske, who was in command of the government's second line, quickly organised the counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

. Huske ordered forward all of Lord Sempill's Fourth Brigade, which had a combined total of 1,078 men ( Sempill's 25th Foot, Conway's 59th Foot, and Wolfe's 8th Foot). Also sent forward to plug the gap was Bligh's 20th Foot, which took up position between Sempill's 25th and Dejean's 37th. Huske's counter formed a five battalion strong horseshoe-shaped

Many shapes have metaphorical names, i.e., their names are metaphors: these shapes are named after a most common object that has it. For example, "U-shape" is a shape that resembles the letter U, a bell-shaped curve has the shape of the vertical ...

formation which trapped the Jacobite right wing on three sides.

Jacobite collapse and rout

With the collapse of the left wing, Murray brought up the ''Royal Écossais'' and Kilmarnock's Footguards, who were still unengaged, but when they had been brought into position, the Jacobite first line had beenrout

A rout is a panicked, disorderly and undisciplined retreat of troops from a battlefield, following a collapse in a given unit's command authority, unit cohesion and combat morale (''esprit de corps'').

History

Historically, lightly-equi ...

ed. The ''Royal Écossais'' exchanged musket fire with Campbell's 21st and commenced an orderly retreat, moving along the Culwhiniac enclosure to shield themselves from artillery fire. Immediately, the half battalion of Highland militia, commanded by Captain Colin Campbell of Ballimore, which had stood inside the enclosure ambushed them. In the encounter, Campbell of Ballimore was killed along with five of his men. The result was that the ''Royal Écossais'' and Kilmarnock's Footguards were forced out into the open moor and were engaged by three squadrons of Kerr's 11th Dragoons. The fleeing Jacobites must have put up a fight since Kerr's 11th recorded at least 16 horses killed during the entirety of the battle.

The Irish Picquets under Stapleton bravely covered the Highlanders' retreat from the battlefield, preventing the fleeing Jacobites from suffering heavy casualties. That action cost half of the 100 casualties that they suffered in the battle. The ''Royal Écossais'' appear to have retired from the field in two wings; one part surrendered after suffering 50 killed or wounded, but their colours were not taken and a large number retired from the field with the Jacobite Lowland regiments. A few Highland regiments also withdrew in good order, notably Lovat's first battalion, which retired with colours flying. The government dragoons let it withdraw, rather than risk a confrontation.

Ruthven Barracks

Ruthven Barracks (), near Ruthven in Badenoch, Scotland, are the best preserved of the four barracks built in 1719 after the 1715 Jacobite rising. Set on an old castle mound, the complex comprises two large three-storey blocks occupying two side ...

, and the remains of the Jacobite right wing also retired southwards. The MacDonald and the other Highland left-wing regiments, however, were cut off by the government cavalry and were forced to retreat down the road to Inverness. The result was that they were a clear target for government dragoons. Major-General Humphrey Bland

Lieutenant General Humphrey Bland (1686 – 8 May 1763) was an Irish professional soldier, whose career in the British Army began in 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession and ended in 1756.

First published in 1727, his ''Treatise of Mili ...

led the pursuit of the fleeing Highlanders, giving " Quarter to None but about Fifty French Officers and Soldiers".Reid (2002), pp. 80–85.

Conclusion: casualties and prisoners

Jacobitecasualties

A casualty, as a term in military usage, is a person in military service, combatant or non-combatant, who becomes unavailable for duty due to any of several circumstances, including death, injury, illness, capture or desertion.

In civilian usa ...

are estimated at between 1,500 and 2,000 killed or wounded, with many of them occurring in the pursuit after the battle. Cumberland's official list of prisoners taken includes 154 Jacobites and 222 "French" prisoners (men from the "foreign units" in the French service). Added to the official list of those apprehended were 172 of the Earl of Cromartie's men, captured after a brief engagement the day before near Littleferry

Littleferry ( gd, Am Port Beag) is a village on the north east shore of Loch Fleet in Golspie, Sutherland, and is in the Scottish council area of Highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated ...

.

In striking contrast to the Jacobite losses, the government losses were reported as 50 dead and 259 wounded. Of the 438 men of Barrell's 4th Foot, 17 were killed and 104 were wounded. However, a large proportion of those recorded as wounded are likely to have died of their wounds. Only 29 men out of the 104 wounded from Barrell's 4th Foot later survived to claim pensions, and all six of the artillerymen recorded as wounded later died.

Several senior Jacobite commanding officers were casualties, including Keppoch; Viscount Strathallan {{Use dmy dates, date=November 2019

The title of Lord Maderty was created in 1609 for James Drummond, a younger son of the 2nd Lord Drummond of Cargill. The titles of Viscount Strathallan and Lord Drummond of Cromlix were created in 1686 for Willia ...

; Commissary-General Lachlan Maclachlan; and Walter Stapleton, who died of wounds shortly after the battle. Others, including Kilmarnock

Kilmarnock (, sco, Kilmaurnock; gd, Cill Mheàrnaig (IPA: ʰʲɪʎˈveaːɾnəkʲ, "Marnock's church") is a large town and former burgh in East Ayrshire, Scotland and is the administrative centre of East Ayrshire, East Ayrshire Council. ...

, were captured. The only high-ranking government officer casualty was Lord Robert Kerr

Lord Robert Kerr (died 16 April 1746) was a Scottish nobleman of the Clan Kerr and the second son of William Kerr, 3rd Marquess of Lothian. His family's surname at the time he lived was often also spelt as 'Ker'.

He is thought to have gone on a gr ...

, the son of William Kerr, 3rd Marquess of Lothian

William Kerr, 3rd Marquess of Lothian, ( – 28 July 1767) was a Scottish nobleman, styled Master of Jedburgh from 1692 to 1703 and Lord Jedburgh from 1703 to 1722.

Early life

He was the son of William Kerr, 2nd Marquess of Lothian and Lady Jean ...

. Sir Robert Rich, 5th Baronet

Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Rich, 5th Baronet (1717 – 19 May 1785) was a British Army general and Governor of Londonderry and Culmore.

He fought at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 as colonel of the 4th King's Own (Barrell's) Regiment, where h ...

, who was a lieutenant-colonel and the senior officer commanding Barrell's 4th Foot, was badly wounded, losing his left hand and receiving several wounds to his head. A number of captains and lieutenants had also been wounded.

Aftermath

Collapse of Jacobite campaign

As the first of the fleeing Highlanders approached Inverness, they were met by the 2nd battalion of Lovat's regiment, led by the Master of Lovat. It has been suggested that Lovat shrewdly switched sides and turned upon the retreating Jacobites, an act that would explain his remarkable rise in fortune in the years that followed.Reid (2002), pp. 88–90. Following the battle, the Jacobites' Lowland regiments headed south towards Corrybrough and made their way to Ruthven Barracks, and their Highland units made their way north towards Inverness and on through to Fort Augustus. There, they were joined by Barisdale's battalion of Glengarry's regiment and a small battalion of MacGregors. At least two of those present at Ruthven, James Johnstone and John Daniel, recorded that the Highland troops remained in good spirits despite the defeat and eager to resume the campaign. At that point, continuing Jacobite resistance remained potentially viable in terms of manpower. At least a third of the army had either missed or slept through Culloden, which along with survivors from the battle gave a potential force of 5,000 to 6,000 men. However the roughly 1,500 men who assembled at Ruthven Barracks received orders from Charles to the effect that the army should disperse until he returned with French support.Roberts (2002), pp. 182–83. Similar orders must have been received by the Highland units at Fort Augustus, and by 18 April, the majority of the Jacobite army had been disbanded. Officers and men of the units in French service made for Inverness, where they surrendered as prisoners of war on 19 April. Most of the rest of the army broke up, with men heading for home or attempting to escape abroad, although the Appin Regiment amongst others was still in arms as late as July. Many senior Jacobites made their way to , where Charles Edward Stuart had first landed at the outset of the campaign in 1745. There, on 30 April, they were met by two Frenchfrigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s: the ''Mars'' and ''Bellone''. Two days later, the French ships were spotted and attacked by three smaller Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

: the ''Greyhound

The English Greyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, the breed has seen a resurge ...

'', ''Baltimore'', and '' Terror''. The result was the last real engagement of the campaign. During the six hours in which the battle continued, the Jacobites recovered cargo that had been landed by the French ships, including £35,000 of gold.

With visible proof that the French had not deserted them, a group of Jacobite leaders attempted to prolong the campaign. On 8 May, nearby at Murlaggan, Lochiel, Lochgarry, Clanranald and Barisdale all agreed to rendezvous at Invermallie on 18 May, as did Lord Lovat

Lord Lovat ( gd, Mac Shimidh) is a title of the rank Lord of Parliament in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1458 for Hugh Fraser, 1st Lord Lovat, Hugh Fraser by summoning him to the Scottish Parliament as Lord Fraser of Lovat, altho ...

and his son. The plan was that there they would be joined by what remained of Keppoch's men and Macpherson of Cluny's regiment, which had not taken part in the battle at Culloden. However, things did not go as planned. After about a month of relative inactivity, Cumberland moved his army into the Highlands, and on 17 May, three battalions of regulars and eight Highland companies reoccupied Fort Augustus. The same day, the Macphersons surrendered. On the day of the planned rendezvous, Clanranald never appeared and Lochgarry and Barisdale showed up with only about 300 combined, most of whom immediately dispersed in search of food. Lochiel, who commanded possibly the strongest Jacobite regiment at Culloden, mustered 300 men. The group dispersed, and the following week, the government launched punitive expeditions into the Highlands that continued throughout the summer.

After his flight from the battle, Charles Edward Stuart made his way towards the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

, accompanied by a small group of supporters. By 20 April, Charles had reached Arisaig

Arisaig ( gd, Àrasaig) is a village in Lochaber, Inverness-shire. It lies south of Mallaig on the west coast of the Scottish Highlands, within the Rough Bounds. Arisaig is also the traditional name for part of the surrounding peninsula south ...

on the west coast of Scotland. After spending a few days with his close associates, he sailed for the island of Benbecula

Benbecula (; gd, Beinn nam Fadhla or ) is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2011 census, it had a resident population of 1,283 with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It is in a ...

in the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coast ...

. From there, he travelled to Scalpay, off the east coast of Harris

Harris may refer to:

Places Canada

* Harris, Ontario

* Northland Pyrite Mine (also known as Harris Mine)

* Harris, Saskatchewan

* Rural Municipality of Harris No. 316, Saskatchewan

Scotland

* Harris, Outer Hebrides (sometimes called the Isle of ...

, and from there made his way to Stornoway

Stornoway (; gd, Steòrnabhagh; sco, Stornowa) is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis and Harris in Scotland.

The town's population is around 6,953, making it by far the largest town in the Outer Hebrides, as well a ...

. For five months, Charles crisscrossed the Hebrides, constantly pursued by government supporters and under threat from local laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in ...

s, who were tempted to betray him for the £30,000 upon his head.Prebble (1973), p. 301. During that time, he met Flora Macdonald

Flora MacDonald ( Gaelic: ''Fionnghal nic Dhòmhnaill'', 1722 - 5 March 1790) was a member of Clan Macdonald of Sleat, best known for helping Charles Edward Stuart evade government troops after the Battle of Culloden in April 1746. Her famil ...

, who famously aided him in a narrow escape to Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye (; gd, An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or ; sco, Isle o Skye), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated b ...

. Finally, on 19 September, Charles reached Borrodale on in Arisaig, where his party boarded two small French ships, which ferried them to France.Harrington (1991), pp. 85–86. He never returned to Scotland.

Repercussions and persecution

The morning after the Battle of Culloden, Cumberland issued a written order reminding his men that "the public orders of the rebels yesterday was to give us

The morning after the Battle of Culloden, Cumberland issued a written order reminding his men that "the public orders of the rebels yesterday was to give us no quarter

The phrase no quarter was generally used during military conflict to imply combatants would not be taken prisoner, but killed.

According to some modern American dictionaries, a person who is given no quarter is "not treated kindly" or "treated ...

". Cumberland alluded to the belief that such orders had been found upon the bodies of fallen Jacobites. In the days and weeks that followed, versions of the alleged orders were published in the ''Newcastle Journal'' and the ''Gentleman's Journal''. Today, only one copy of the alleged order to "give no quarter" exists. It is, however, considered to be nothing but a poor attempt at forgery since it is neither written nor signed by Murray, and it appears on the bottom half of a copy of a declaration published in 1745. In any event, Cumberland's order was not carried out for two days after which contemporary accounts report that for the next two days the moor was searched, and many of those wounded were put to death. The orders issued by Lord George Murray for the conduct of the aborted night attack in the early hours of 16 April suggest that it would have been every bit as merciless. The instructions were to use only swords, dirks and bayonets, to overturn tents and subsequently to locate "a swelling or bulge in the fallen tent, there to strike and push vigorously".Roberts (2002), pp. 177–80. In total, over 20,000 head of livestock, sheep, and goats were driven off and sold at Fort Augustus

Fort Augustus is a settlement in the parish of Boleskine and Abertarff, at the south-west end of Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands. The village has a population of around 646 (2001). Its economy is heavily reliant on tourism.

History

The Gaeli ...

, where the soldiers split the profits.

While in Inverness, Cumberland emptied the

While in Inverness, Cumberland emptied the jail

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correc ...

s that were full of people imprisoned by Jacobite supporters by replacing them with Jacobites themselves. Prisoners were taken south to England to stand trial for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. Many were held on hulks on the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

or in Tilbury Fort

Tilbury Fort, also known historically as the Thermitage Bulwark and the West Tilbury Blockhouse, is an artillery fort on the north bank of the River Thames in England. The earliest version of the fort, comprising a small blockhouse with artil ...

, and executions took place in Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

, York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

and Kennington Common

Kennington Common was a swathe of common land mainly within the London Borough of Lambeth. It was one of the earliest venues for cricket around London, with matches played between 1724 and 1785.G B Buckley, ''Fresh Light on 18th Century Cricket'' ...

. The common Jacobite supporters fared better than the ranking individuals. In total, 120 common men were executed, one third of them being deserters from the British Army. The common prisoners drew lots amongst themselves, and only one out of twenty actually came to trial. Although most of those who stood trial were sentenced to death, almost all of them had their sentences commuted to penal transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their ...

to the British colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

for life by the Traitors Transported Act 1746 (20 Geo. II, c. 46). In all, 936 men were thus transported, and 222 more were banished Banished may refer to:

* ''Banished'' (TV series), a 2015 drama television series

* ''Banished'' (film), a 2007 documentary

* ''Banished'' (video game), a city-building strategy game by Shining Rock Software

* Banished (Halo), an alien faction ...

. Even so, 905 prisoners were actually released under the Act of Indemnity that was passed in June 1747. Another 382 obtained their freedom by being exchanged for prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

being held by France. Of the total 3,471 prisoners recorded, nothing is known of the fate of 648. The high-ranking "rebel lords" were executed on Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher grou ...

in London.

Following up on the military success won by their forces, the British government enacted laws to further integrate Scotland, specifically the Scottish Highlands, with the rest of Britain. Members of the Episcopal clergy were required to give oaths of allegiance to the reigning Hanoverian dynasty. The Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746

The Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746 (20 Geo. II c. 43) was an Act of Parliament passed in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising of 1745 abolishing judicial rights held by Scots heritors. These were a significant source of power, especia ...

ended the hereditary right of landowners to govern justice upon their estates through barony courts. Prior to the Act, feudal lords

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

(which included clan chiefs) had considerable judicial and military power over their followers such as the oft-quoted power of "pit and gallows". Lords who were loyal to the government were greatly compensated for the loss of these traditional powers. For example, the Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll ( gd, Diùc Earraghàidheil) is a title created in the peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The earls, marquesses, and dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerful ...

was given £21,000. The lords and clan chiefs who had supported the Jacobite rebellion were stripped of their estates, which were then sold and the profits were used to further trade and agriculture in Scotland

Agriculture in Scotland includes all land use for arable, horticultural or pastoral activity in Scotland, or around its coasts. The first permanent settlements and farming date from the Neolithic period, from around 6,000 years ago. From the begi ...

. The forfeited estates were managed by factors

Factor, a Latin word meaning "who/which acts", may refer to:

Commerce

* Factor (agent), a person who acts for, notably a mercantile and colonial agent

* Factor (Scotland), a person or firm managing a Scottish estate

* Factors of production, suc ...

. Anti-clothing measures were taken against the Highland dress

Highland dress is the traditional, regional dress of the Highlands and Isles of Scotland. It is often characterised by tartan (''plaid'' in North America). Specific designs of shirt, jacket, bodice and headwear may also be worn along with clan ...

by an Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

in 1746. The result was that the wearing of tartan

Tartan ( gd, breacan ) is a patterned cloth consisting of criss-crossed, horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours. Tartans originated in woven wool, but now they are made in other materials. Tartan is particularly associated with Sc ...

was banned except as a uniform for officers and soldiers in the British Army and later landed men and their sons.

Culloden battlefield today

Today, a

Today, a visitor centre